STEAM OPERATIONS

OF THE

CHESAPEAKE &OHIO RAILWAY

AT

by

William E. Simonton, III

Last Updated 01/11/2011

|

Home |

Steam Operations |

Drawings |

Typical Heavyweight Passenger Car Consists

1940's |

Contact |

| Numbered Structures | A.F.E. Map Revisions | Articles |

Notes | Things to Come | What's New | Photos |

STEAM OPERATIONS 1930-1956

In the middle and late 1940's, Hinton was one of the C&O's busiest terminals. The railroad supported a population of approximately 8,000 based upon the 1930 Sanborn Map. The most recent reported population is 2,532. In addition to being a crew change point for all passenger and freight movements, Hinton originated eastbound coal extras, local passenger trains, and local freight trains. All these operations required numerous engine changes and were an interesting aspect of the yard operation. Passenger trains used Pacific 4-6-2s and Hudson 4-6-4s on the New River Subdivision, and Mountain 4-8-2s and Greenbrier 4-8-4s on the Alleghany Subdivision. The C&O's only dual purpose steam locomotives, the Kanawha class 2-8-4s were used on both subdivisions in passenger service, however, only K-4's (2730 and 2760 series) equipped for passenger service with signal and steam lines were used east of Hinton if sent east on a passenger train. All passenger trains with more than 12 heavyweight cars were double headed on the Alleghany Subdivision. Manifest freights were assigned Kanawha's on the New River Subdivision and 2-6-6-6 Alleghenies on the Alleghany Subdivision. Occasionally, a fast manifest freight rated a T-1 2-10-4 from Russell, Kentucky. Coal trains used one Allegheny on the New River Subdivision and two on the Alleghany–one on the head end and a pusher. Local freights were powered by 2-8-0s, 2-8-2s or 2-6-6-2 Mallets. Prior to the arrival of the H-8's beginning in early 1942, H-7 2-8-8-2s were the workhorses at Hinton. All extras were identified with the engine number and direction, i.e., Extra 1600 Eastbound, would be an eastbound extra headed up by Engine Number 1600 (an H-8 2-6-6-6). No mine shifters worked out of Hinton.

Officials included a General Yardmaster, Assistant General Yardmaster and Terminal Trainmaster. Each trick (shift) had a yardmaster at the station, a yardmaster at Avis Crossing and assistant yardmasters at CW Cabin and MX Cabin. There were four switch crews per trick, one crew for each end of both yards - the east (Avis) yard and the west (Hinton) yard. Both 0-8-0s and Class C-12 0-10-0s worked the yards.

Steam switcher locomotives were oriented so that the crew was switching on the front of the locomotive. At the beginning of each trick the crew working the west end of the Avis yard would pick up a supply of cabooses from the caboose tracks in the west yard and take them to Avis. Cabooses were delivered to the crews, and if the switch crew ran out of cabooses they would return for a new supply. It must be remembered however that it was standard C & O practice to assign a caboose to a conductor and the cabooses were not randomly assigned to crews

PASSENGER TRAINS

All through passenger trains changed locomotives and crews at Hinton. Engines for the eastbound trains were moved by a hostler and switch tender from the eastbound ready tracks in front of the yard office to the "middle track" of the three tracks at the station and were spotted an engine length east of the crossovers east of the depot. Double-headed engines were coupled together on the engine ready tracks prior to being moved onto the middle track. Arriving eastbound trains were stopped with the locomotive clear of the crossover; the locomotive was uncoupled and run through the crossover onto the middle track, and then backed to clear the crossover. The relief crew boarded the relief locomotive after it was spotted by the hostler on the middle track and moved it back through the crossover to couple onto the eastbound passenger train. After the train departed the hostler moved the locomotive west on the thoroughfare track or "pit track" as it was know at Hinton to the engine terminal area (pit). Eastbound local passenger trains which terminated at Hinton arrived on the middle track at the station, and the crew went off duty there.

Locomotives for westbound through passenger trains were spotted on the engine ready tracks west of the station, and the road crew boarded the locomotive there. Westbound passenger trains stopped with the locomotive clear of the switch leading to the engine terminal tracks, the crew was relieved, a hostler moved the light engine to the service tracks, and the road crew backed onto the train and departed down the New River. Westbound locals which originated at Hinton made-up in the yard and were spotted on the westbound main at the station for boarding. The locomotive was coupled to the train by the hostler, and the road crew boarded the locomotive at the station.

The C & O laid over two diners every night at Hinton. The C & O served meals on a schedule on its name trains The George Washington, The Fast Flying Virginian, and The Sportsman. The diners on The George Washington traveled all the way from Washington to Cincinnati, but the diners on the Sportsman (two sections) and the F.F.V. (two sections) were only on those trains during meal times. Laying the diners over at Hinton permitted the C & O to service eight trains (4 east and 4 west) with seven (7) diners and permitted the diner crews to sleep at night off the railroad. [16]

The two diners were stored on a short siding near the station and next to the ice house to permit each to be iced by its top loading bunkers (similarly to reefers).

FREIGHT TRAINS

Westbound freight trains arriving at Hinton stopped with the locomotive at the station, the crew was relieved by a hostler who ran the train into the west yard and then took the locomotive to the engine terminal. If no hostler was available, the yardmaster would instruct the road crew to move the train into the yard. The crew on the caboose also was relieved at the station. Crews for westbound freights down the New River boarded the locomotive at the engine supply house, moved to the train, and departed down river past CW Cabin.

Because of the grade and curve at the station, eastbound arriving freights were not stopped at the station, and the road crew put the train in the east yard at Avis Crossing and MX Cabin. If the train was too long for the yard track, the road crew would double the required number of cars from the head end onto a second track. The road crew uncoupled the locomotive, returned to the station on the No. 1 main track (the westbound main), and spotted the locomotive there for the hostler to pickup.

Locomotives for eastbound freights departing Hinton were boarded by road crews at the engine ready tracks in front of the yard office. If the train was leaving from the short tracks at the east yard (yard tracks 1-5) the locomotive moved from the station up the middle track and ran through a empty short track, usually No. 1, to get to the head end of the train.

Locomotives for freight trains departing the long east yard tracks, ran east on the eastbound main track (No. 2 Main) to MX Cabin and backed from there to the train. Pushers for coal trains were called for the same time as the headend crew. The pusher crew boarded its locomotive at the engine ready tracks, picked up its caboose at the caboose tracks in the west yard and ran up the middle track to couple onto the rear of the train. The pusher was turned at Alleghany and returned to Hinton as a light engine move with no caboose.

SCHEDULED TRAINS

Passenger Schedule: August, 1945

--

Locals Hi-Lighted.

Typical 1940's Passenger Car Consists

with car assignments.

Time Freight Train Schedule:

January, 1949

|

Arv. Lv. |

TIME |

TRAIN HINTON |

FROM |

TO |

NOTES |

|

A |

12:15a |

90 |

Chicago |

Richmond |

“The Expediter” |

|

A |

12:44a |

2 |

Cincinnati |

Washington |

“The George Washington” |

|

L |

12:53a |

2 |

|

|

|

|

A |

1:03a |

42 |

Cincinnati |

Newport News |

|

|

L |

1:10a |

42 |

|

|

|

|

A |

1:15a |

41 |

Newport News |

Cincinnati |

|

|

L |

1:20a |

41 |

|

|

|

|

A |

1:35a |

1 |

Washington |

Cincinnati |

“The George Washington” |

|

L |

1:40a |

1 |

|

|

|

|

L |

1:45a |

90 |

Chicago |

Richmond |

“The Expediter” |

|

A |

2:00a |

93 |

|

|

|

|

L |

3:00a |

93 |

|

|

|

|

A |

4:53a |

4 |

Cincinnati |

Washington |

"The Sportsman" |

|

L |

5:00a |

4 |

|

|

|

|

A |

5:00a |

94 |

|

|

|

|

L |

5:30a |

7 |

Hinton |

Cincinnati |

Originates

Hinton |

|

A |

5:37a |

46 |

Detroit |

Newport News |

|

|

L |

5:45 |

46 |

|

|

|

|

L |

6:00a |

94 |

|

|

|

|

A |

6:35a |

16 |

Huntington |

Charlottesville |

|

|

L |

6:45 |

16 |

|

|

|

|

A |

7:10a |

43 |

Newport News |

Cincinnati |

“Fast Flying Virginian”• |

|

L |

7:15a |

43 |

|

|

|

|

A |

8:03a |

3 |

Washington |

Cincinnati |

“Fast Flying Virginian”• |

|

L |

8:10a |

3 |

|

|

|

|

A |

10:30a |

98 |

Stevens, KY |

Potomac Yard |

Fast Manifest Freight |

|

A |

8:45a. |

103 |

West Bound Mail |

All Mail Train |

|

|

L |

9:00a |

103 |

All Mail Train | ||

|

L |

12:01p |

98 |

|

|

|

|

A |

12:15 p |

104 |

East Bound Mail |

All Mail Train |

|

|

L |

12:30p |

104 |

East Bound Mail |

All Mail Train | |

|

A |

1:05p |

14 |

Huntington |

Hinton |

Terminates Hinton # |

|

A |

1:30p |

13 |

Charlottesville |

Huntington |

|

|

L |

1:35p |

13 |

|

|

|

|

L |

2:30p |

99 |

Hinton |

Russell, KY |

Boxcar Pickup |

|

A |

2:45p |

95 |

|

|

|

|

L |

4:30p |

95 |

|

|

|

|

A |

5:30p |

92 |

|

|

|

|

A |

6:25p |

8 |

Cincinnati |

Hinton |

Terminates Hinton |

|

A |

7:21p |

6 |

Cincinnati |

Washington |

“Fast Flying Virginian” |

|

L |

7:30p |

6 |

|

|

|

|

L |

7:30p |

92 |

|

|

|

|

A |

7:45p |

47 |

Newport News |

Detroit |

|

|

L |

7:50p |

47 |

|

|

|

|

A |

8:05p |

5 |

Washington |

Cincinnati |

|

|

L |

8:25p |

5 |

|

|

|

| L | 8:40p | 15 | Hinton | Huntington |

Originates Hinton # |

- No. 43 was consolidated with No. 3 at Huntington # Sometimes referred to unofficially as the West Virginian

In addition to the above scheduled trains a number of extras were run. Tidewater coal amounted to as many as twelve trains each day with ten being typical. An equal number of empty hoppers would return westbound, and a light pusher locomotive from each coal train would return to Hinton. Coal trains and empty hopper trains were generally dispatched to run behind passenger trains and manifests so that slower trains were not overtaken by faster moving traffic. Coal trains were usually not dispatched from Hinton unless the coal movement could get to the siding at Alleghany ahead of the following train. There were some coal and manifest movements up the Greenbrier Subdivision for interchange with the Western Maryland at Durbin, amounting to about one extra per day out of Hinton.

Contrary to what one might think, hoppers from several other coal field railroads were no strangers to Hinton. Virginian, Berwind, and a few Western Maryland brought down or destined for the Western Maryland via the Greenbrier Branch were regular visitors to Hinton. Surprisingly, quite a bit of coal was sent up the Greenbrier Branch destined for the Western Maryland at Durbin. One Extra per week powered by a 2-6-6-2 with about 35-40 cars. A mine on the C&O had the contract to provide coal to the huge West Virginia Pulp & Paper mill at Luke, Maryland.

The local freights for the New River and Alleghany subdivisions were called at Hinton in the late morning and the locals from Handley and Clifton Forge would arrive at Hinton in the late afternoon or early evening. When a shipload of iron ore destined for Ashland, Kentucky arrived at Newport News, there would be a flurry of westbound ore trains over the mountain and through Hinton.

As can be inferred from the schedule and the comments, the railroad was operated almost as two single tracked railroads--one eastbound and one westbound. Most mainline crossovers had speed limits of 15 m.p.h. and in some areas trains running "against the current of traffic," e.g., running on the wrong main had general speed restrictions. However, the railroad was heavily signaled with numerous interlocking plants and trains were run either direction on either main as necessary to keep traffic moving.

ENGINE SERVICING

The following applies to operations after 1929-30 when the West Yard at Hinton was completely rebuilt. Before 1930, locomotives at Hinton were coaled from a wooden ramp style coal dock which apparently dated from the latter part of the 19th century. Only a drawing of the trestle ramp has so far turned up in the materials received from CSX.[1] In 1929 Fairbanks Morse & Company built a 800-ton coal dock[2], a 200-ton sand bunker, and installed two 60 cubic foot double track Universal cinder conveyors[3], and other subcontractors built the engine inspection pits, engine supply & ice house, coal dock foreman's office, and wash rack. C&O forces probably installed what appears to be a modified single Robertson? cinder conveyor which was used on one track, and it was likely just moved from another location.

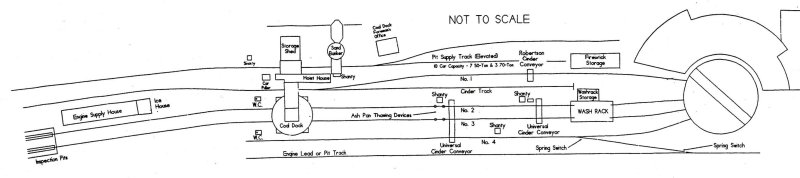

Figure 1 Engine Servicing Area "Pit"

Eastbound and westbound engines entering the service facilities at Hinton all proceeded west of the Grand Central Yard Office (assistant yard foreman's office), and entered the service tracks at the crossovers in front of and west of the Grand Central Yard Office. To allow movement of engines through the yard a thoroughfare track, or "pit track" as it was called at Hinton was provided. Engines coming in off the Alleghany Subdivision (westbound) were not turned prior to servicing, and backed through the inspection pits, coal dock, and wash rack. The process began at the engine inspection pits just west of the engine supply house. Inspectors with a light and a hammer crawled over and under the engines looking for any worn or broken parts. Steam engines, particularly passenger engines, threw a layer of oil on to all their working parts. The engine inspector's job was therefore the dirtiest job on the railroad. While being inspected, the engine oil reservoirs were filled and the engine oiled. There was no check list for the inspectors--everything was checked. If a problem was found, such as a broken spring, a report was filed at the engine inspectors office in the engine supply house, and that report was sent by vacuum tube to the roundhouse office. More than 90% of all steam locomotives inspected required some maintenance or repair in the roundhouse before being ready to return to operation. Normally an engine could be expected to spend two hours after each run in the roundhouse for repairs and maintenance - the most common being repair to the brakes or replacement of the brake shoes.

Except for oil tanks in the basement, the engine supply house, by the late 1940s did not store much in the way of parts. Only air hose, glad hands, water glasses, coupler knuckles, and other easily changed parts were maintained. Much of the space was used by road enginemen waiting for their westbound engines after reporting in at the roundhouse and getting their assignments. Ready engines were brought to the north side (railroad direction) of the engine supply house by a hostler, ice provided for the crew, and the crew would board its engine. Just west of the engine supply house were engine ready tracks for storing road ready but not yet needed engines for the New River Subdivision (westbound). Normally two or three machinist to inspect the engines and one engine supply man to fill the mechanical lubricators with oil at the engine worked the inspection pit. The engine supply man also checked each engine to make sure that the emergency tool kit, composed of one 18 inch pipe wrench, a hammer, a chisel, red flags, and flares, was complete.

After inspection, the engines proceeded to the coal dock to take on water, coal and sand. The coal dock and sand bunker were constructed by Fairbanks Morse & Company of reinforced concrete with standard appliances.[4] The hoist house contained three electric motors--two to power the skip hoist winches and one to power the crusher in the pit which operated from a linkage to the motor in the hoist house. The only other motor was for the sorting grates in the monitor of the coal dock. The coaling chutes are asymmetrical due to the fact that Hinton coal dock had two internal bins--one for 200 tons of lump coal and the second for 600 tons of stoker coal. The 200 ton bin occupied the eastern one-fourth of the coal dock next to the sand bunkers and coaled all four tracks. The 600 ton bin coaled the two inside tracks from the center bay of the coal dock and the outside tracks from the west exterior coaling chutes.

The tracks at the coal dock were numbered 1 through 4. No. 1 was the track under the skip hoist elevator shaft and No. 4 was the outside track on the south side of the coal dock. The pit track was just south[5] of No. 4. No. 4 was used principally for refueling engines requiring a quick turn-around. To assist the process, two spring switches were installed just east of the coal dock to redirect engines coming off the turntable or from the west on No. 4, immediately back onto the pit track.[6] The foreman could then easily tell the engine hostler to put the engine on No. 1 with very little chance of misunderstanding. Numbers 2 and 3, through the center of the coal dock, were the inbound tracks. Two engine coalers were used, and they usually took turns spotting the engines and filling the water tanks, coal bunker, and sand bunkers.

To supply the coal dock, two to four laborers were kept busy dumping and elevating coal. In the summer hoses were used to wash the coal from the cars and keep down the dust, but in the winter it was necessary for the labors to break the coal lose with picks and shovels. In very cold weather fires on steel plates were kept burning along side the hoppers on the pit supply track to warm the coal and assist the laborers in cleaning the coal from the hoppers. The fuel supply track was on a slight incline with an approximate maximum height of five feet at the end next to the arch brick storehouse. A car puller was located just west of the coal dock pit. The car puller was used move cars off the pit and properly spot cars which had not stopped just right to avoid using an engine. If no more than three of the hoppers were the longer 70 ton cars, the fuel track held ten hoppers, and when one was needed, a laborer would uncouple it and ride it to the pit--stopping it with a the hand brake. A set of bells was mounted on the wall of the coal dock hoist house to give warning that a car was being rolled by gravity down to the pit. On one occasion, the limit of no more than three 70 ton hoppers was not observed, and at least one ended up in a newly-installed electrical shop in the west end of the arch brick store house. The electrical shop was quickly moved.

In 1946 additional sand storage was added to the two 10 ton dry sand bunkers on the coal dock by extending the tops of the bunkers with a steel addition. The increased volume would have created an additional capacity of 6 tons each. This also resulted in additional walkways that create the unique appearance at Hinton. Although the coal dock was retired in 1960, the sanding facilities were used to sand diesels until 1986. Also in 1946, the sand bunker was modified by moving the sand conveyor from the inside of the structure to the enclosed structure on its north face, and building a new sand pit on a separate spur track. In addition to increasing the capacity of the sand bunker, the change would have alleviated the problems sure to have been encountered with the coal pit and sand pit on the same spur so close together. This change was probably brought about as a result of the dry sand capacity of the C&O H-8 2-6-6-6 locomotives with their large sand boxes (eight tons total) and the pace of war time traffic.

After receiving water, coal, and sand the engines would proceed to the cinder conveyors. After 1943 Hinton used one three-track Universal cinder conveyor [tracks 2, 3 & 4], one two-track Universal cinder conveyor [tracks 2 & 3][8], and one modified single Robertson? Cinder Conveyor [track 1]. An excellent photograph of the east Universal and modified Robertson cinder conveyors is provided by C&OHS photograph CSPR 281. (See Drawings Page). Originally both 60 cubic foot capacity Universal cinder conveyors were two track models servicing the two in-bound tracks. In 1943 the west Universal cinder conveyor was extended to the allow dumping cinders from a locomotive setting on the No. 4 coaling track.[9] As hot as a steam engine was, in very cold weather the ash pans could freeze, and oil burning ash pan thawing devices were provided on the inbound tracks next to the west Universal cinder conveyor.[10] At the cinder conveyors the grates would be shaken, the fire cleaned of any clinker, and the cinders dumped into the under-track cinder dollies.

Three laborers worked each fire pit -- one shaking grates, one cleaning the fire and one blowing cinders from the engine ash pans. Fairbanks Morse & Company sold a mechanism to collect and hold the cinders if the cinder dolly was not properly positioned on multiple track cinder conveyors,[11] and Hinton apparently had those devices on the original two tracks of the F-M cinder conveyors, the third track which was added when one cinder conveyor was extended in 1943 lacked that device. On more than one occasion, the laborers ended up in the pit shoveling cinders out by hand. A bad load of coal could create a serious clinker buildup in an engine firebox. Despite grate shakers, stoker bars, and cutter bars, it was sometimes not possible to break up the buildup without dropping the fire.

After emptying the ash pans, the engines proceeded to the wash rack where two laborers, one on each side, washed the engine wheels and side rods with very hot, high-pressure water and atomized detergent oil. The wash rack was retired with the advent of diesels with their traction motors. After washing, the engines were moved by a hostler to the 115 foot turntable and placed in a roundhouse stall for the needed repairs. Seventy to one hundred locomotives passed through the pit area in a 24-hour period.

The engine ready tracks for eastbound engines (Alleghany Subdivision) were two tracks in front of the yard office. Water standpipes were provided, and engine men waiting for eastbound engines waited at the yard office. If the regular engine ready tracks were full, the pit track would also be used to store ready engines. The caboose tracks were tracks 9 and 10 just west of the scale house (Building #33).[12]

In addition to the servicing outlined above, Hinton's 17-stall roundhouse was equipped with wheel drop pits for removing trucks and drivers and could do almost any repair up to and including Class IV repairs (heavy boiler work such as replacing super heater tubes). By all reports it was always full as fully ninety percent of steam locomotives coming in from the road needed some repairs or maintenance in the roundhouse.

The other major repair and maintenance facility was the mallet engine house. It received a concrete floor in the late 1930's and was subsequently modified at some point thereafter so that the track running through the mallet house was used as a lubrication bay for mallet engines with air operated grease guns to permit rapid turn around. Non-articulated engines were seldom lubricated in the mallet engine house - that was done in the roundhouse during repairs. The stub end track was used as the spring shop. As a result of the dynamics of a rod steam locomotive, enormous stress was put upon the springs and equaling systems. If it did not break, the equalizing system could literally wear out. The Mallet Engine House was retired about 1959 and razed.

Steam operations required other car movements on a regular basis as a normal part of providing fuel and supplies to the various engines and service areas. As noted, the engine supply house had oil tanks in the basement and would have required regular refills by a tank car. A connector was provided for that purpose on the railroad south side of the building. In addition, ice would have been regularly delivered by box car to the ice house.

The coal dock required on average 170 50-ton hopper cars per week to be delivered to the coal pit track, and on occasion as many as 10 50-ton hoppers were elevated on one shift. Two hundred and fifty to three hundred tons of wet sand was used each week and was delivered in open hoppers to the spur behind the sand bunker. The sand bunker held (as built) 200 tons of wet sand, but it is well to remember that the sand boxes of each H-8 held 8 tons of dry sand. To dry the sand, four sand drying stoves were continuously kept red hot. As the sand dried, it collected in large tank in the floor of the sand bunker. As it accumulated, the tank would descend and trip a mechanism which closed a rubber saucer shaped valve, and the sand was automatically blown by high pressure air to the dry sand bunkers on the coal dock.[13] In addition, Hinton generated 25 tons of cinders per week which was moved in dedicated hoppers marked "Cinders Only." The spur behind the arch brick storehouse required movements over the coal dock pit to deliver fire brick, parts, and supplies to the round house, to remove the scrap car every 3-4 months, and to supply detergent oil by tank car to an under ground tank next to the engine wash house about once a month.

The main shops received some supplies from a short spur off the freight house spur which ran up the hill behind the roundhouse. The short spur was used for hoppers for a coal conveyer to supply the power house and to a coal house (building #83) behind the roundhouse which supplied coal to the blacksmith shop and roundhouse via a chute into the rear of the blacksmith shop. A spot was provided for a hopper to receive cinders delivered by a vacuum system from the power house[14], and a spot was provided for a tank car to deliver lamp and engine oil by gravity into three six thousand (6000) gallon tanks behind the shops. These tanks had been removed from the basement of the oil supply house in 1941, and placed outside next to the power house.[15] One 50-ton hopper of coal was required every three for four days for the power house depending on the weather. When one looks at the additional car and engine movements required, one can begin to appreciate the scope of activity that were the Hinton shops in the steam era.

Steam operations ended on the C&O in 1956 with Hinton seeing the last of the H-8 2-6-6-6s under steam on the New River Subdivision between Hinton and Handley in July of that year. The Hinton shops are now mere memories to generations of C&O railroad workers who are rapidly dwindling, and a few latter day researchers such as the author who can sometimes recreate Hinton in its heyday in his minds eye, or the case of Jim EuDaly, his model railroad. Of the service facilities at Hinton, only the coal dock, sand bunker, coal dock foreman's office, engine supply house, yard office, master mechanic's office, pump house and ice house and a few miscellaneous structures remained as of August 1995. Except for the mainline tracks and passing siding, all the tracks have been removed from the west yard. Soon only the massive concrete coal dock and smaller sand bunker will bear witness to what was, and even those may disappear if CSX decides that they are attractive nuisances which are better removed from the property.

The author would like to thank W. S.

"Sims" Wicker former Yard Master at Hinton and a C & O employee

from 1925 to 1972, Charles Hannah, former pit foreman at Hinton for sharing

their memories of the steam era, the C & O Historical Society, and Thomas

W. Dixon, Jr., who over the last thirty-five years have provided the author

with copies of Hinton drawings as the Archive cataloging process has proceeded,

and Jim EuDaly who shared his research on Hinton

train movements.

Copyright 2003 William E.

Simonton, III

[1] C

& O Drawing No. 884, formerly 943.

[2] A

few partial Fairbanks Morse & Company drawings have been located in the COHS

Archives.

[3] Author's

conclusion based upon photographs, drawings of the Universal Cinder Conveyors

at Stephens Yard, Kentucky, which shared common designs with Hinton, the

drawing of the 1943 extension to the Hinton cinder conveyor C & O Drawing

No. 18098-A, and Fairbanks Morse & Co. Bulletin No.

73001, Locomotive Coaling Stations, reprinted by TLC Publishing, Rt. 4, Box

154, Lynchburg, VA 24503.

[4] See

Fairbanks Morse & Co. Bulletin No. 73001, ibid.

[5] All

directions are railroad directions. Due

to a loop in the New River at Hinton, railroad east is almost due west and

railroad west is almost due east.

[6] See

drawing showing location of spring switches.

[7] Known

date of other improvements to the service facilities in the West Yard at

Hinton.

[8] See

photograph in December 1990 Railroad Modeling Magazine.

[9] C

& O Drawing No. 18098-A.

[10] C &

O Drawing No. 9440.

[11] Fairbanks

Morse & Company Bulletin No 76003, ibid.

[12] W. S.

"Sims" Wicker, Conversation on August 1, 1992.

[13] Charles

Hannah, Letter of September 4, 1992.

[14] Note on

C & O construction drawings of the power house.